In the thirty years of my life, I have experienced different phases of digital evolution. Born at the beginning of the dotcom bubble, our world has transitioned to social media popularisation, followed by the artificial intelligence (AI) hype, integration and advancement. Eleven years ago, when I began my undergraduate studies, I was recommended to, and ended up, studying quantitative social science, given how many UK professors acknowledged that purely qualitative and humanities scholars could hardly survive under the big data epoch. Fast forward to today, and the same could be said about AI: We either learn and practise it, or we are phased out.

With the latest available data, we can easily visualise a Venn Diagram. The population using the Internet reaches 6.04 billion worldwide (meaning 73.2% of the global population, according to Kepios). Within these 6.04 billion people, 5.66 billion (meaning 68.7% of the global population, according to Kepios) are social media users. Also, within the 6.04 billion people, 900 million actively use AI, accounting for some 11% of the global population.

AI-Driven High-Stakes Career Divergence

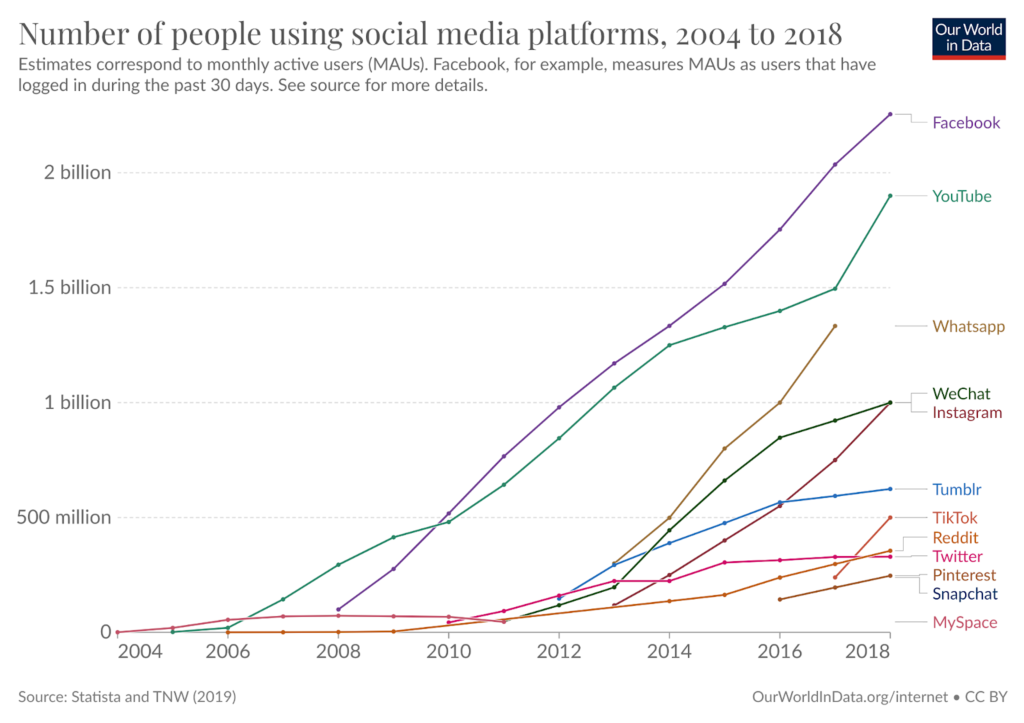

Our World in Data indicates that MySpace was the first social media to reach a million monthly active users—it achieved this milestone in 2004. Around that time, we witnessed the start of the social media era. If we take a look at Figure 1, we can see that social media popularisation experienced an exponential growth between 2004 and 2018. This gives us an insight into how the AI growth trajectory could look in another decade or longer. At least for now, it appears that the gap between the global population of active social media and AI users will be closing, as the former is saturated to a large degree while the latter is rapidly emerging.

Figure 1: Number of people using social media platforms, 2004 to 2018

Estimates correspond to monthly active users (MAUs), Facebook, for example, measures MAUs as users that have logged in during the past 30 days.

Source: Statista and TNW (2019)

Given its rapid growth and integration, recent Western commentary suggests that the labour market is already experiencing effects related to AI. In a recent US survey, 9.3% of domestic companies reported that they had used generative AI in production during the last two weeks. Such a figure offers an implication: in frontier AI economies like the US, while the AI hype is heightened, domestic companies’ AI adoption rate still has significant room for growth—and likely an exponential one if we learn from the historical records of the dotcom and social media patterns.

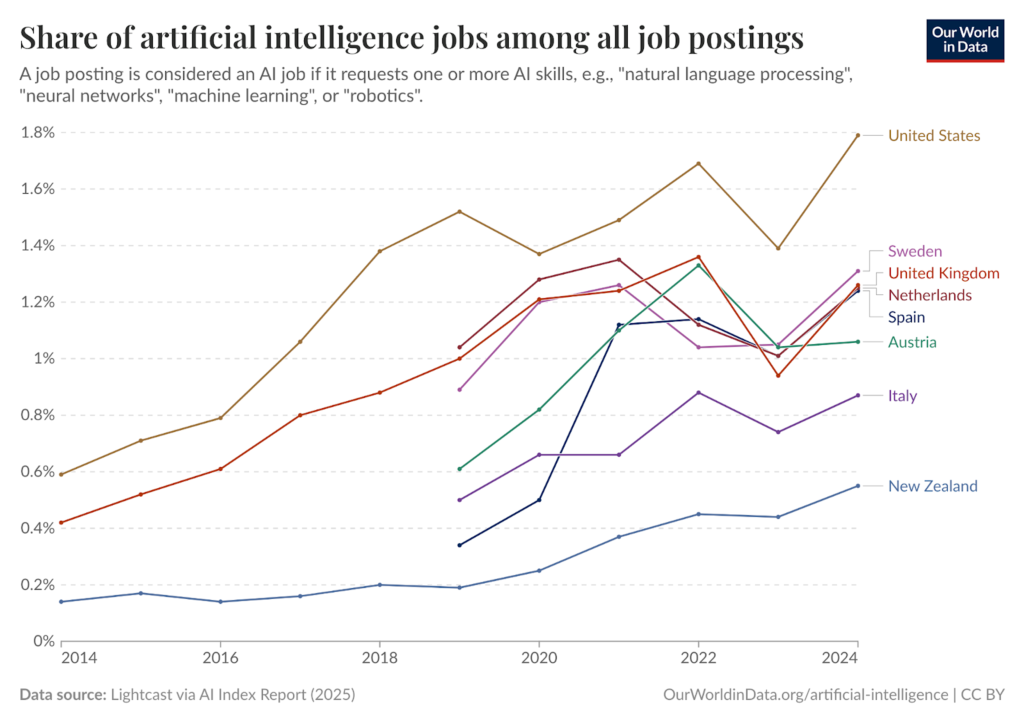

Goldman Sachs Research argues that, to date, the AI adoption of US companies remains very low. When contemporaneous technological adoption rates are low while such technology is expected to trend towards exponential growth in usage, the young labour force is positioned in a sweet spot for AI upskilling and professional adoption. Otherwise, they are at risk of facing occupational and economic downward mobility in the long run. Figure 2 tells us that the proportion of available AI jobs among all job postings grew modestly and constantly between 2014 and 2024 in major Western economies. Other than the US, other major Western economies had around 1% or less of the share of AI jobs among all job postings in 2024. Figure 2 further supports the argument that the young labour force is at a point of separation: Many could survive and thrive when climbing up the professional ladder, while others could be subject to downward mobility, depending on how determined and resilient they are in adopting and applying AI technology at work as AI demand rates in the labour markets continue to rise.

Figure 2: Share of AI jobs among all job postings

A job posting is considered an AI job if it requests one or more AI skills, e.g., “natural language processing”, “neural networks”, “machine learning”, or “robotics”.

Data source: Lightcast via AI Index Report (2025)

Point of Separation: Individual-Level Disparities

At such a point of separation, we can foresee a growth of individual-level and country-level disparities. I have spent 11 years conducting econometric modelling and analysis. Since I have transitioned into an AI safety researcher, I have, in addition, focused on AI modelling using machine learning techniques. Researchers know very well how the additions of parameters and subsequent ingestions of more data for training always lead to better and more predictive models. This means, with more parameters used in model training, AI models and agents are becoming increasingly powerful and capable, resulting in more productivity at work.

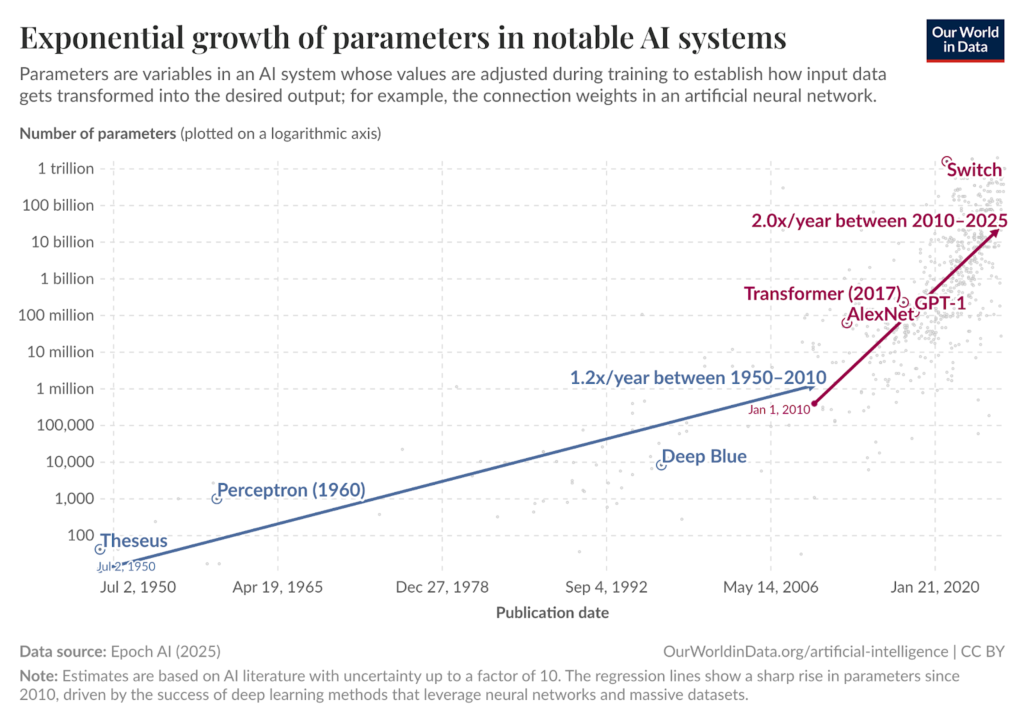

Figure 3 presents the exponential growth of parameters in notable AI systems (plotted on a logarithmic axis). We can see that the annual growth of parameters in notable AI systems advanced from 1.2 times per year, between 1950 and 2010, to 2.0 times per year, between 2010 and 2025. Statistically speaking, the exponential growth of parameters in notable AI systems has accelerated drastically since 2010. This means, AI models and agents have exponentially been more powerful and capable, especially in the post-2010 epoch. As the massive exponential growth of AI power and capability goes, those who are fully adopting and integrating AI technology at work would benefit from productivity, creativity, and intelligence boosts. On the contrary, those who are lagging in AI adoption are increasingly more likely to be phased out in the labour market as time goes on.

Figure 3: Exponential growth of parameters in notable AI systems

Parameters are variables in an AI system whose values are adjusted during training to establish how input data gets transformed into the desired outputs: for example, the connection weights in an artificial neural network

Daa source: Epoch AI (2025)

Point of Separation: Country-Level Disparities

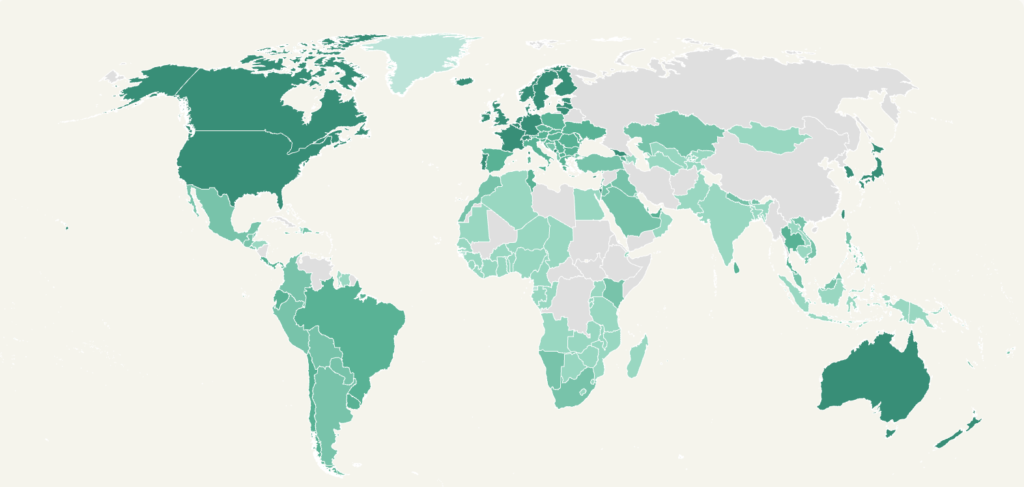

Beyond individual-level discussion, country-level disparities are concerning too. Figure 4 shows the global usage index of Claude. The darker green the countries are, the more likely their populations (per capita) are to use Claude. We can see that countries with the highest per capita usage rate of Claude are major Western powers and other advanced frontier AI economies, led by Israel, Singapore, and Japan. It is noteworthy that in accordance with international sanctions and Anthropic’s commitment to supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity, the Claude services are not available in areas under Russian occupation. Furthermore, the Claude services are not available in China.

As we can see from Figure 4, developing and emerging regions are far less likely to use Claude services, compared to their advanced and frontier AI counterparts. This indicates the imbalanced global distribution of Western AI services’ accessibility. Of course, Figure 4 alone does not necessarily suggest that developing and emerging economies’ populations are subject to AI technology-marginalisation and discrimination. One of the reasons is that, in the geoeconomic and geopolitical landscapes, Western resources are usually disproportionately shared among Western powers and a few other advanced economies, while the Chinese Government is targeting its global connections and influences in the developing regions. This means, even if Western AI services are disproportionately less likely to be used in the developing regions, these populations may, over time, be more likely to use the Chinese AI counterparts.

Figure 4: Global usage index of Claude

Data source: Anthropic Economic Index (2025)

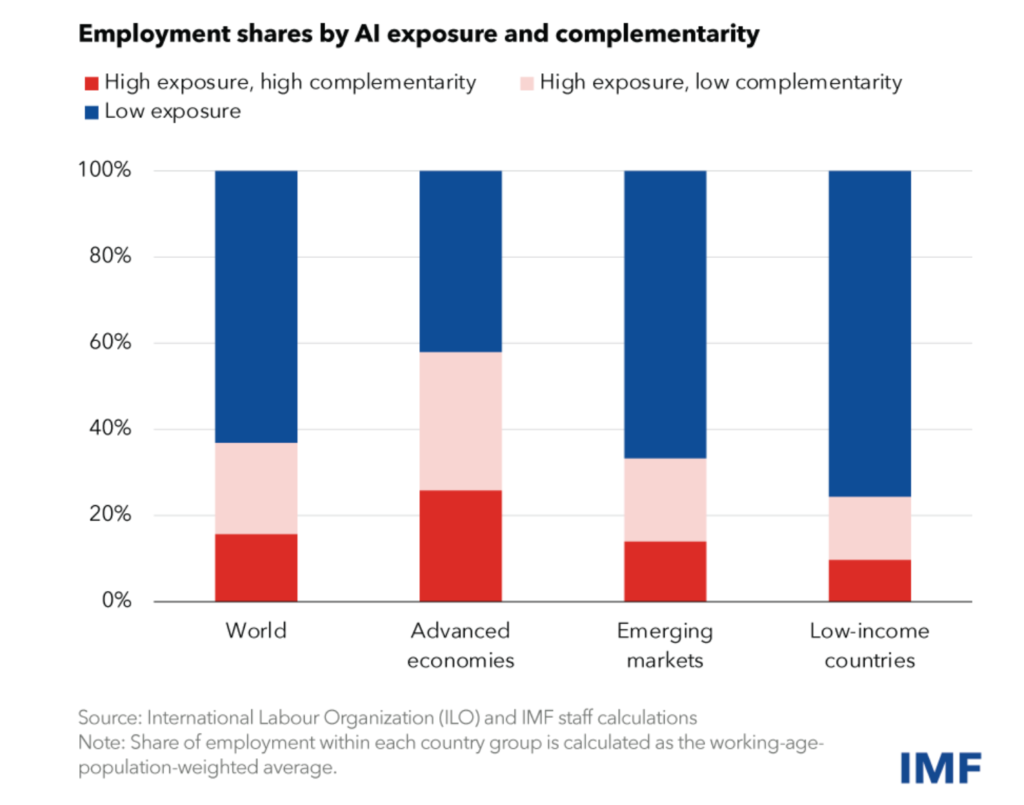

In econometric analysis, I particularly specialise in panel data analysis looking at within-country and between-country nuances. Applying similar terminologies, we can see (1) between-country and (2) within-advanced-economy AI impacts on global disparities. Figure 5 informs how AI impacts our jobs. Employment opportunities that are high exposure and high complementarity to AI mean jobs that can and will be highly AI-integrated, which complement rather than threaten the human labour force. Employment opportunities that are high exposure but low complementarity to AI refer to jobs that can and will be highly AI-integrated, which threaten rather than complement the human labour force. Employment opportunities that are low exposure to AI, in addition, are jobs that are unlikely to be affected by AI advancement and popularisation. We see that most employment opportunities that are highly AI-integrated and complement rather than threaten the human labour force are concentrated among advanced economies. These employment opportunities are least likely to be available in low-income countries. Such between-country global economic inequalities may worsen as AI integration progresses in the labour markets.

Moreover, when looking at within-advanced-economy AI impacts, we see that advanced economies also share the most employment opportunities that are highly AI-integrated which threaten rather than complement the human labour force (Figure 5). In these advanced economies, a 2024 International Monetary Fund report states that lower-skilled labour forces are more likely to be threatened by AI integration in the labour markets than their high-skilled counterparts. Such a circumstance deepens existing economic inequalities between skilled and less-skilled labour forces in advanced economies. Given the fact that the speed of AI advancement continues to accelerate, such long-term AI-induced economic inequalities may plausibly worsen more than currently expected.

Figure 5: AI’s impact on jobs

Most jobs are exposed to AI in advanced economies, with smaller shares in emerging markets and low-income countries.

Data source: International Labour Organisation and International Monetary Fund (2024)

Policy Implications

AI is, and will continue to be, tightly tied to economic competitiveness at both the individual and country level, just like what the dotcom and social media historical records told us. Not only is AI adoption heading towards a diverged path, but the AI-induced gaps, as the above figures imply, are deepening. As of writing this piece, AI upskilling is, to a large extent, a personal choice. Media and commentary simply warn us that AI upskilling and adoption are going to be necessary for upward trajectories, professionally or nationally, and it is up to us—the mass population—to build our AI proficiency or not. Yet, for years to come, governments cannot simply launch AI schemes or opportunities for their young labour force to incentivise the voluntary building and application of their AI skillsets. Governments will have to mandatorily require educational institutions and corporate entities to design AI-focused education curricula and on-the-job training programmes, respectively. Moreover, if AI-induced economic inequalities continue to exacerbate, individual governments have to prepare the responsive social protection and labour protection policy adjustments, in order to provide a safety net for those who are negatively impacted by AI the most. Learning the use of social media or not a decade ago did not determine any individual or national productivity much. However, whether countries and their populations are AI-literate and even skilled or not could decide their long-term social standing.